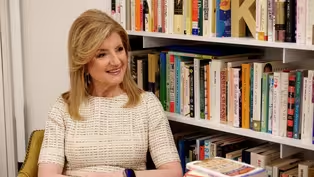

Arianna Huffington

Season 6 Episode 9 | 25m 48sVideo has Closed Captions

CEO of Thrive Global, Arianna Huffington, on beating burnout with behavioral change.

CEO of Thrive Global, Arianna Huffington, gives her take on making it in America: behavioral changes through microsteps. She believes that for humans, downtime is a feature—not a bug. She urges us not to buy into the collective delusion that in order to succeed, we have to be “on” 24/7. Instead, invest in our physical and mental wellbeing as a pathway to healthier and happier lives.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Arianna Huffington

Season 6 Episode 9 | 25m 48sVideo has Closed Captions

CEO of Thrive Global, Arianna Huffington, gives her take on making it in America: behavioral changes through microsteps. She believes that for humans, downtime is a feature—not a bug. She urges us not to buy into the collective delusion that in order to succeed, we have to be “on” 24/7. Instead, invest in our physical and mental wellbeing as a pathway to healthier and happier lives.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Tell Me More with Kelly Corrigan

Tell Me More with Kelly Corrigan is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipWe've talked a lot in this series about the interplay between agency, circumstance, and intervention.

When it comes to intervention, some people will tell you the very best person to intervene is you.

Can you get more deep sleep?

Can you drink less?

Eat more whole foods?

Can you walk around the block once a day?

Stop looking at your phone.

Make your relationships deeper and more connected.

Arianna Huffington is a girl from Greece who watched "Laugh-In" to learn English, a Cambridge grad who taught herself public speaking by joining debate, a storyteller who made a superblog that went global.

And she has one big idea for making it in America.

Behavior change through micro steps.

I'm Kelly Corrigan, this is "Tell Me More," and here is my conversation with entrepreneur, proud Greek, and every bit her mother's daughter, Arianna Huffington.

[Theme music playing] ♪ Yay!

Hi.

How are you?

Great to have you.

Come on up.

Before you moved here, what was your dream of America?

What did you think you were getting to?

I loved America before I came here.

There was this incredible land of endless opportunities and dreams realized.

And right now, I believe we just need to change direction.

And part of that is an individual journey.

But we also need to stop treating each other so harshly.

We need to give each other grace.

We are in the middle, Kelly, of a huge cultural transformation, and it goes back to the first industrial revolution, when we started revering machines.

And the goal with machines, and after machines, software, is to minimize downtime.

But the human operating system is different.

For the human operating system, downtime is a feature, not a bug.

And the data is absolutely clear.

So, if we can convince people, obviously they are going to be healthier and happier, but they are also going to be more productive, because productivity is also about creativity and innovation.

These are the characteristics that first disappear when you are depleted and exhausted.

You may still be able to do transactional things, but you are not going to be your best, creative, most productive self.

We all have so much evidence of that from our own lives, from the lives of people we know and love.

I have a lot of evidence from being on the board of Uber, and one of the cultural values is working harder, smarter, longer.

And I remember telling the board, you know, smarter and longer are contradictions... [Laughs] and there are diminishing returns.

Yeah.

I'm curious about your childhood in Greece.

Tell me about your mom and your dad.

My parents separated when I was 11, so, my sister and I lived with my mom in a one-bedroom apartment.

She was like the foundation of everything.

She basically, I think, really believed that if you didn't eat every 20 minutes, something terrible would happen to you.

[Laughs] So, the center of our home was the kitchen.

Yeah.

And conversations around the kitchen table.

And she never went to college, but she was a voracious reader, learner, loved philosophy.

And so, there were these big, existential conversations ever since we were little... Yeah, around the table, and I think probably one story that sums her up is I was coming back from school, and I saw a magazine cover in a newspaper kiosk on the way that had a picture of Cambridge University in England.

I knew nothing about it, but something really drew me to it, and I came home and I put it on the kitchen table-- I bought it--and said to my mom, "I want to go there."

[Laughs] And my mom was the only person who said, "Well, let's find out how you can go there."

Everybody else said, "Don't be ridiculous.

"You don't speak English.

We don't have any money.

And it's hard even for English girls to get into Cambridge."

But my mother figured it out.

What really distinguishes her is that she made me feel that if I didn't get into Cambridge, not a big deal, that this was an adventure.

Yeah.

And life was full of adventures, and we're going to make the journey fun.

And if I didn't get in, there would be another adventure.

Yeah.

Which is so true.

And then you went to Cambridge.

And then I went to Cambridge.

And you did debate.

And I fell in love with the debating society, the Cambridge Union.

I had no idea that this was a big deal in England.

You know, the Cambridge Union and the Oxford Union and many prime ministers had been there.

Their famous debates.

I just fell in love with it.

And so, I wanted to learn to speak.

I was a terrible speaker and I had an extremely heavy accent, even heavier than now, and also at a time and in a country where accents were ridiculed.

Oh.

So, people literally would laugh at me when I would get up to speak.

But I persevered, and I never missed a debate.

I loved the spectacle of people's hearts and minds being moved by words.

You know, a friend of mine put my name down for what they call the Standing Committee, which was the lower rung of the ladder, while I was in London, and by the time I came back, I couldn't take my name off the printed ballots, and I thought this would be humiliating, and I came up first among the standing committee members, and suddenly I was launched on a path that made me president of the Cambridge Union, which was definitely a huge pivot in my life.

There was a lot of press around it, because I was the first foreigner and I was the third woman.

I was asked to write a book on it, and that was the changing role of women.

I remember getting that letter from an English publisher and I responded, "Thank you so much, but I can't write."

[Laughter] And he responded, "Can you have lunch?"

[Laughter] He took me to lunch and he offered me a modest advance.

I remember it was £6,000, which I thought would help me live a modest life while I was writing the book, and he actually said, he said, "Listen, if you can't write, I won't publish it."

And I lost £6,000.

So, so, that became my first book when I was 23.

"The Female Woman."

It's interesting, I think, for all people to think about the moment or moments in which they started to take themselves seriously, as someone who could do things, you know, who could write a book or be the president of the debate society, or even go to Cambridge in the first place.

And maybe that goes back to your mom.

Definitely.

And the fact that at the center of her relationship with me was so much unconditional loving.

And the fact that I knew that if I didn't get into Cambridge, if I didn't become president, if I didn't have a book that was published, she wouldn't love me any less.

And she used to call it like "We are held by the universe."

And she made you feel you're being held by the universe, and it doesn't mean that everything is going to go your way.

Not at all.

But whatever happens, you're being held by the universe.

Even when bad things happen to us, we may not know why.

And a lot of things, she used to say, don't make sense while you're living them.

They will make sense looking back.

After coming out of this very warm parent relationship and into Cambridge, which was such a success for you, and into the book, then you really fell for the American way of doing things, which is work hard, work long, don't look up, don't smell the flowers, it's all passing fast, it's a dog-eat-dog world.

After this book, I-- I was asked constantly to write more books on women, but literally, I had literally nothing else to say.

Yeah.

Yeah.

And instead, I locked myself up and wrote a book on the crisis in political leadership-- I studied economics at Cambridge-- which nobody wanted to publish.

It was rejected by 36 publishers.

I ran out of money by then.

Again, that was another moment, another pivotal moment when I was depressed.

I thought, this is it.

This was just an accident.

I have to go get a real job.

And I was passing by Barclays Bank on St. James's Street in London, where I lived, and something made me go in and ask to see the manager and armed with absolutely nothing except Greek chutzpah, ask him for a loan, and he gave it to me.

And his name is Ian Bell, and I still send him a holiday card, because it was really what allowed me to keep things together until the book finally got published.

It was not a success, but it was published, and it kept me on the path of being a writer.

And then I wrote biographies of Maria Callas and Picasso.

I wrote a book on Greek mythology.

I wrote political books, and by 2005, I launched the Huffington Post.

Can I ask you?

About the Huffington Post, there were so many people who had more or less the same idea at more or less the same time, which is content is king.

Now we have this fabulous thing called the internet.

Let's marry it up together and we'll get 100 million readers every day.

But so few people actually got that dream across the finish line.

Do you have feelings or theories about why HuffPo worked?

I think it was really a combination of taking the internet very seriously, and taking a lot of people who are friends to take it seriously.

So, literally, I sent emails out to 500 friends or acquaintances inviting them to write, and my pitch was, you're busy, you're Arthur Schlesinger or you're Larry David, and things happen in the world and you have something to say, and sure, the "New York Times" could publish it, but that's a process.

You have to submit it, you're going to be edited, and you don't really want to bother.

You just want to dash off 500 words or 700 words or 200 words and have your view inserted into the cultural bloodstream in real time.

And people got it.

And so, what happened is that we elevated blogging.

I mean, HuffPost was the first online site to win a Pulitzer.

So, we didn't just want to do blogging.

We wanted to combine that with great investigative journalism and offer people an opportunity to share their thoughts.

So, we had all these famous people, but we also invited anyone who wanted to write to be able to do so.

I think there's a combination of these things.

Plus, frankly, not giving up when things were tough at the beginning, because I still remember some of the reviews, day one.

One of them, by Nikki Finke, was "The Huffington Post is an unsurvivable failure.

"It is the movie equivalent of "Gigli," "Ishtar," and "Heaven's Gate" all rolled into one."

[Laughter] So, two years after starting the Huffington Post, you collapsed and you broke your cheekbone and sort of came to with blood everywhere in your office.

Yes.

What happened is that I had really bought into the collective delusion that in order to be this super founder of the Huffington Post and a super mom of two daughters, divorced, I didn't have the luxury to take care of myself, to sleep, to eat, write, anything.

And by 2007, in April, I literally collapsed and hit my head on my desk and broke my cheekbone.

And that was the beginning of my wake-up call, both about my own life but also about the world.

I was literally diagnosed with burnout, and at the time, 2007, burnout was not a word that was in the cultural vocabulary.

Yeah.

But being a bit of a nerd, once I was diagnosed with that, I started investigating the phenomenon.

Saw it was a global epidemic.

It wasn't just my personal problem.

So, I started covering all these issues exhaustively on the Huffington Post.

In 2007, we launched a dedicated sleep section, and I remember very well a board meeting where my board members complained, "Why is a political site launching a dedicated vertical," as we call them, "on sleep?"

This frothy, silly topic.

Mm-hmm.

But I had read the science.

Sleep wasn't a frothy, silly topic.

So, we started covering all these issues.

Sleep, stress, food, movement, everything.

Ironically, though, what happened is that suddenly we started getting so much traffic... Uh-huh.

for these issues and so much advertising, a lot more advertising than we ever got for our political coverage.

Yeah.

So, the shareholders and the board members began to realize that even if they didn't believe in it, it was good for the business.

By 2011, we sold to AOL, which I really wanted, because I wanted us to keep growing faster than we had the resources to do, and I wanted to grow internationally, I wanted to grow in video, and I wanted to do it all at once rather than sequentially.

So, the agreement was that I would continue running it, and I wanted to.

I had no intention of ever leaving the Huffington Post.

And what changed is that by 2016, I realized that it wasn't enough to raise awareness around these topics, which I could have continued doing...

Forever.

through the Huffington Post forever.

I wanted to help people change behaviors, and that's so much harder.

I know.

And for that, you need a dedicated behavior change technology company.

So, that was a really hard decision, because I loved the Huffington Post.

It was like a third child for me.

I never thought I would have another career.

So, that's what made me decide to leave and launch Thrive Global in 2016.

Our mission was to end the stress and burnout epidemic.

Again, burnout wasn't much discussed until 2019, when the World Health Organization acknowledged it for the first time as an occupational hazard.

Oh, interesting.

And then, of course, came the pandemic, which was a huge accelerant for us.

Yeah.

And, again, if it were not for my mother, I wouldn't have taken that risk, because, Kelly, there is absolutely no guarantee of success.

I mean, I left a super successful global media company with 850 journalists in 18 countries to go start again, literally.

Go rent a room, raise money, hire people.

But one of the other things my mother would always say is never worry about failure.

She would call failure not the opposite of success, but a stepping stone to success.

Totally.

You know, it reminds me of something that's come up in other conversations, which is the impact of your zip code versus the impact of your genetic code.

The story we were telling people was, well, you're gonna end up like your parents.

Yes.

But when there's one change agent inside a community, it can spread.

When people put on solar panels, it's enormously contagious.

When people get electric vehicles, it's hugely contagious.

Like, as soon as we break the seal on a new behavior, it has a tremendous ripple effect.

First of all, it's very important to stress that everything we are talking about is not an alternative to policy changes.

It's not an alternative to addressing social determinants of health.

What's a piece of policy that you are dying to see get passed?

I'm dying to--to see universal child care.

I think it's one of the hugest problems.

And with our foundation, we worked on that during the pandemic.

You had nurses and health care providers, not to mention many other ordinary people who couldn't go to work because they didn't have anybody to leave their child with.

And--and schools were closed.

And now that we know so much about how important the early years are... That's another bit of science it seems like we're ignoring.

Yes.

Is the first 36 months.

The first 36 months.

And knowing, you know, that in the end, if you don't start things right, there are consequences.

And the consequences in terms of health are going to bankrupt Western civilization.

There is absolutely no way we are going to be able to address the growing increases, not just here, globally, around chronic stress-related diseases.

Plus, our mental health crisis.

That's 90% of our health care spending.

I know.

I had that written down that it's 3.8 trillion.

90% is mental health and chronic...

Chronic diseases.

Do you think insurance companies will ever get involved and say that "We'll start funding things that are pre-disease," or will we just wait for everybody to get sick before we start dealing with it?

Well, that is the key.

And we are talking to some health care companies that are also seeing that things are not working.

I know, because I've read about a study in an article you wrote about these veterans who had lung cancer, and then they--some of them were given mental health services, and they had a 30% reduction in morbidity, and the guy you quoted said, "If this was a pill"...

Yes.

"We'd have a trillion- dollar valuation."

There's also studies about how to sort of surround a patient with the right messages and support, and there was a study that I read about in another piece you wrote that-- where they set up barber shops to support people with high blood pressure.

Well, it's actually they didn't set up barber shops.

They went to barber shops.

They worked with barber shops.

Basically.

It's like meeting people where they are.

People are in barber shops.

They trust their barber.

And it's amazing.

Doctors who are also community activists would go there and talk to them and tell them what they need to do.

Sometimes, it involves taking a drug.

But hypertension kills millions of people and it's eminently...

Preventable.

Preventable.

But even if you have it, it's eminently treatable.

So, I love that, you know.

Barber shops, churches, temples, schools, you know, basically meeting people where they are.

Because it's micro steps that are sort of integrated into the reality of any given day.

I mean, that's the really big thing that everybody who's ever set a New Year's resolution knows, is that you go too-- everybody goes too big.

Yes.

These small interventions prevent stress from becoming cumulative.

You're never going to eliminate stress from life, but it is cumulative stress that leads to hypertension, that leads to binge eating or binge drinking or not being able to sleep.

Micro steps are not to be underestimated.

Yeah.

We have a thing at "Tell Me More" called Plus One, where we give our guests a chance to shout out somebody who's been instrumental to your well-being or to your thinking.

Who is your plus one?

It has to be my mother, because she was so instrumental to everything and, you know, after she died, interestingly enough, I sadly felt that I had to integrate who she was much more than before, and after she died, I definitely made changes in my life little by little.

Nothing overnight.

Yes.

But again, everything she taught me, interestingly enough, became more present for me after she passed.

While she was alive, I almost felt, "OK, she's got that."

Oh, uh-huh.

Now you carry it.

And now I have to carry it more.

What was her name?

Elli.

Elli.

Here's to Elli.

We have a speed round at "Tell Me More."

Are you ready?

OK. What was your first concert?

Maria Callas.

10 years old.

Spellbinding.

What was your first job?

So, my first job was getting a contract to write a book at 23.

No kidding.

Yes.

What's the best live performance of any kind you've ever seen?

I have to go back to "Norma" and Maria Callas because it stayed in my heart.

Yeah.

What's the last book that blew you away?

A book by Dr. Lisa Miller called "The Awakened Brain."

Oh, sure.

If your high school did superlatives, what would you have been most likely to become?

The tallest journalist.

[Laughs] That's so funny.

We had David Brooks on and he said his would have been the shortest journalist.

Oh, really?

[Laughs] Do you have a favorite celebrity crush?

Garth Brooks.

Right on.

Did not see that coming.

What do you wish you had more time to do?

Read.

Is there anyone you would like to apologize to?

I'm fully current on my apologies.

What's your go-to mantra for hard times?

Rumi.

"Live life as though everything is rigged in your favor."

What's something big you've been wrong about?

Worrying doesn't make things better.

If your mother wrote a book about you, what would it be called?

"She Kept Being Willing to Fail."

If you could say 4 words to anyone, who would you address and what would you say?

I would address my oldest daughter, who is now a mother, and I would say, "When baby sleeps, you sleep."

Uh-huh.

[Laughs] Always onto sleep.

Thank you so much.

It's such a joy to be with you.

Thank you so much, Kelly.

And with you.

Thank you.

Here are my takeaways from my conversation with Arianna Huffington.

Number one, burnout is a global epidemic.

Number two, sleep is far from a frothy, silly topic.

Number 3, when it comes to the human operating system, downtime is a feature, not a bug.

And number 4, when it comes to behavior change, the answer is micro steps.

[Theme music playing] ♪ ♪ ♪

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S6 Ep9 | 59s | Arianna Huffington on downtime in the human operating system as a feature, not a bug. (59s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by: