April 22, 2025

4/22/2025 | 55m 44sVideo has Closed Captions

Rami Jarrah; Geir Pederson; Jon Finer; Abby Edaburn; Jacob Tice

Syrian journalist Rami Jarrah discusses the ousting of Bashar al-Assad by rebel groups. U.N. Special Envoy for Syria Geir Pedersen on this "watershed moment in Syria's history." U.S. Deputy National Security Advisor explains the U.S. angle on developments in Syria. Abby Edaburn and Jacob Tice on their renewed hope for the return of their brother, journalist Austin Tice, believed to be in Syria.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

April 22, 2025

4/22/2025 | 55m 44sVideo has Closed Captions

Syrian journalist Rami Jarrah discusses the ousting of Bashar al-Assad by rebel groups. U.N. Special Envoy for Syria Geir Pedersen on this "watershed moment in Syria's history." U.S. Deputy National Security Advisor explains the U.S. angle on developments in Syria. Abby Edaburn and Jacob Tice on their renewed hope for the return of their brother, journalist Austin Tice, believed to be in Syria.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Amanpour and Company

Amanpour and Company is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Watch Amanpour and Company on PBS

PBS and WNET, in collaboration with CNN, launched Amanpour and Company in September 2018. The series features wide-ranging, in-depth conversations with global thought leaders and cultural influencers on issues impacting the world each day, from politics, business, technology and arts, to science and sports.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipHello everyone and welcome to Amanpour and Company.

Here's what's coming up.

Who's leading the new Syrian government after the Assad dictatorship finally falls?

We asked Syrian journalist Rami Jarrah and about the joy of liberation.

And the sudden collapse that caught almost everyone by surprise.

What chance of an orderly transition?

U.N. special envoy for Syria, Geir Pedersen , joins us.

Then -- It's a moment, a historic opportunity for long-suffering people of Syria.

What of the U.S. role in the region already upended?

I speak to Deputy National Security Advisor John Finer.

Also ahead -- Oftentimes alive, oftentimes treated well.

A mother's hope for an American hostage in Damascus, his siblings join me to speak about journalist Austin Tice, who's been held there since 2012.

"Amanpour and Company" is made possible by the Anderson Family Endowment, Jim Attwood and Leslie Williams, Candace King Weir, the Sylvia A. and Simon B. Poyta Programming Endowment to Fight Anti-Semitism, the Family Foundation of Leila and Mickey Straus, Mark J. Blechner, the Filomen M. D'Agostino Foundation, Seton J. Melvin, the Peter G. Petersen and Joan Ganz Cooney Fund, Charles Rosenblum, Koo and Patricia Yuen, committed to bridging cultural differences in our communities, Barbara Hope Zuckerberg, Jeffrey Katz and Beth Rogers, and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

Welcome to the program, everyone.

I'm Christiane Amanpour in London.

There is a new reality in Syria and the road ahead is still unclear, after rebels swept into the capital Damascus with lightning speed and ended half a century of oppressive rule by the Assad family.

The Kremlin says Vladimir Putin has personally granted Bashar Assad safe haven in Russia.

In Damascus, these were the scenes inside Assad's official residence over the weekend, which rebels and civilians were seen ransacking, while crowds gathered to celebrate in the capital's main square.

Now, back in 2005, shortly after America deposed President Saddam Hussein in neighboring Iraq, I went to Damascus to speak to Assad about clouds gathering over his own head even then.

Mr. President, you know the rhetoric of regime change is headed towards you from the United States.

They are actively looking for a new Syrian leader.

They are granting visas and visits to Syrian opposition politicians.

They are talking about isolating you diplomatically and perhaps a coup d'etat or your regime crumbling.

What are you thinking about that?

I feel very confident for one reason, because I was made in Syria.

I wasn't made in the United States, so I'm not worried.

This is Syrian decision.

It should be made by the Syrian people.

Nobody else in this world.

Well, it took 19 years and a terrible civil war, but the Syrian people have indeed made their decision.

And the rest of the world, taken totally by surprise, is also welcoming this sudden turn of events.

But who exactly are these rebel liberators who include hardline Islamic militants formerly associated with al-Qaeda and ISIS, as well as more moderate factions?

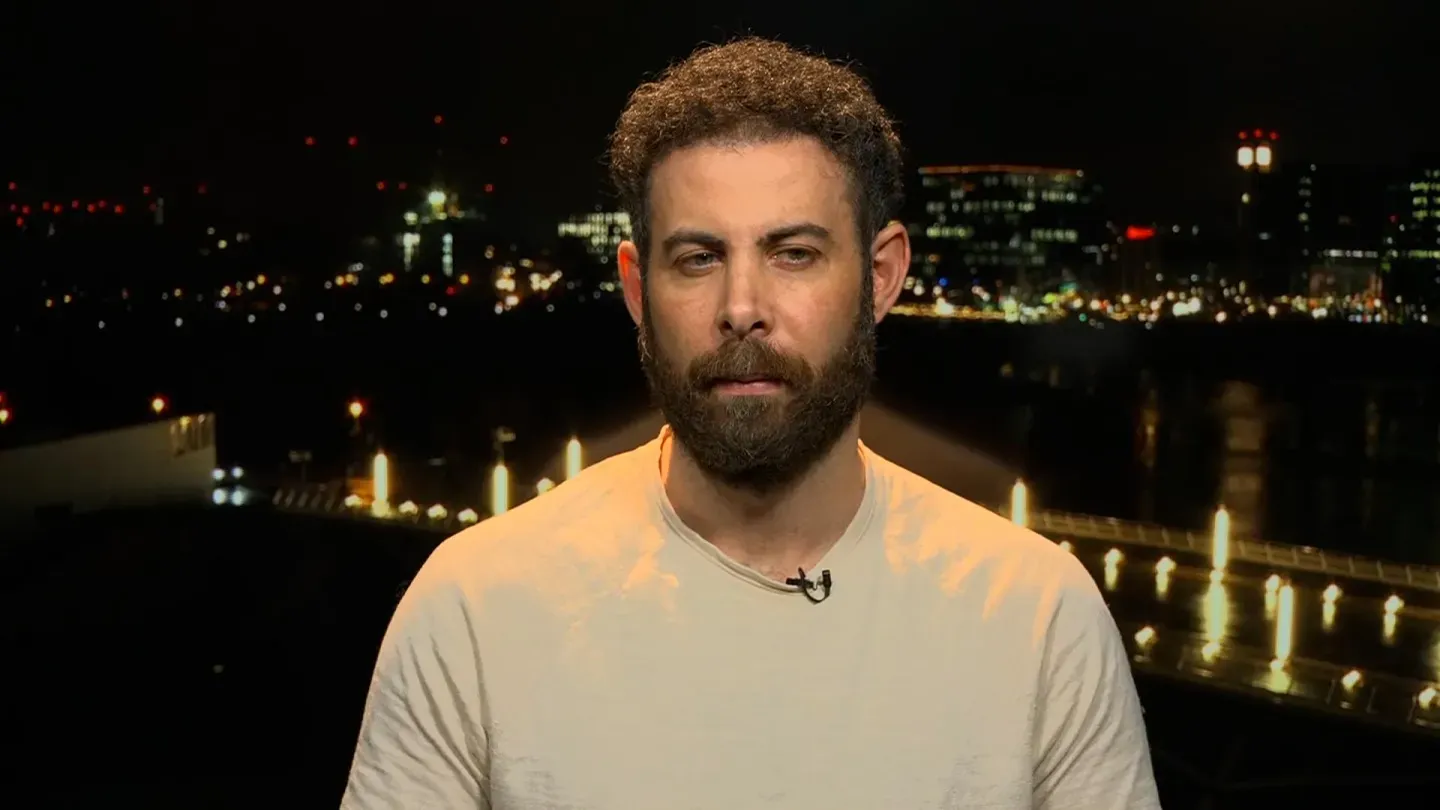

My first guest has reported for years on the human toll of violence in his country, often under a pseudonym for his own safety.

He's journalist Rami Jarrah, who joins me now from Berlin, where he's been in essentially self-imposed exile.

Rami Jarrah, welcome to our program.

And we've spoken to you several times throughout the course of this civil war.

Just tell us, as a Syrian, as somebody who forced - was forced to leave the Assad, you know, civil war, what are you feeling now?

I've been asked that question a lot over the past two days, but honestly, do not have a coherent answer that I can give right now.

Obviously, I'm at joy, but at the same time, I think given the experiences that I speak for many Syrians in saying this, for the past 14 years, we've always, you know, been hopeful.

And then even when events seem to look like they were headed in the right direction, we would, you know, be slapped with a series of very unfortunate events.

And I think that maybe, you know, Syrians generally are traumatized and can't just accept that this one actually looks like it's headed in the right direction.

Only two - just under two weeks ago, Syrian - Syria to me - and, you know, this won't be a popular thing to say, but Syria to me was a distant memory.

It was a subject, a topic that I wanted to avoid.

And that was, you know, the result of many things that went wrong and the basic bleak future that myself and many Syrians, I think, perceived the future would bring.

And Rami, certainly the United States, others in the region, they had pretty much decided that Assad had won this civil war.

And there were all sorts of, you know, interventions to try to rehabilitate him in the Middle East region, to try to bring him on side, you know, by the U.S. for instance, potentially separating him from his main backer, Iran.

What were you hearing - why is it being such a surprise?

How did this rebel coalition, you know, not too far from, you know, inside the border from Turkey do this?

And particularly since the leader, al-Jolani says they've been planning for a year.

Yeah, I mean, it was - I don't want to say that I knew that this planning was going on, but once this offensive started and given the, you know, the links that in general that someone has with those involved, it became very clear to me and I think many people that are able to reach out and get information that this effort had been prepared for quite a while.

I think anyone claiming at this stage that the goal was to take all of Syria and bring down the Assad regime is just taking advantage of being able to say that in hindsight.

I think the reality is that the ambition was to take back some territory.

The name of the offensive indicates that.

It was to basically repel an offensive by the government.

That's the name of the movement.

So, I don't think anyone actually expected that this was going to happen.

And I definitely speak for myself in saying that I never dreamed that this would happen.

But what has been - I mean, if I could just give a quick back story.

Jolani was obviously - had his links to the Islamic State and obviously with al-Qaeda, but he has very pragmatically over the years created these links and then defected from them.

When he pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda, it was basically to protect himself from the Islamic State because he had basically crossed Baghdadi after Baghdadi had sent him to Aleppo.

And then - sorry, to northern Syria to establish the Islamic State there.

And then he broke ties with al-Qaeda.

And first it was just done publicly and then it became an official break of ties.

And what happened after that was that mainly in these past four or five years, Jolani has actually worked with civil society to build an administration of 11 ministries and work with civil society.

And what I'm saying now might sound like I'm actually defending him.

I'm not.

I actually am very skeptical.

I don't trust Jolani.

I think that what he's doing right now is very promising.

We just heard out of Damascus today, I think Damascus, Tartus and Latakia, that a number of laws and guidelines have been set for the fighters that they're not allowed to interfere in civilian life, they're not allowed to tell women what they're allowed to wear or not wear.

These things are all very promising.

Jolani pledging that he's even considering of dissolving HTS is a very promising thing to say, but I think what we need moving forward is action.

And I don't think that -- I don't think it's up to me to decide or suggest that Jolani should be forgiven for what he's done in the past.

But I think the first step that he can take in actually proving that he -- proving the things that he said, that he does -- he respects the aspirations of Syrians who want to see a future democratic state that represents the rights of all Syrians, regardless of sect or ethnicity.

I think the first step in doing that is handing over power to a transitional government and stepping aside.

That's really going to be -- I think that's the best course of action that someone -- Yeah, that will be a test if indeed he has said it and he plans to do that.

We'll see.

Because nobody actually quite -- I mean, I guess he is in charge, but there's no designated leader of the new government as such right now.

But, you know, you say he's done this and that pragmatically.

He is said to have run a very hard line Islamic statelet in Idlib, you know, with maybe not the Taliban exactly, but nonetheless hard line.

And he did speak for the first time since winning Aleppo.

He gave his first interview to CNN's Jomana Karadsheh.

And I just want to play a little bit of what he said to try to, as you say, you know, make himself match this moment.

I believe that everyone in life goes through phases and experiences.

And these experiences naturally increase a person's awareness.

Sometimes it's essential to adjust to reality and because someone who rigidly clings to certain ideas and principles without flexibility cannot effectively lead societies or navigate complex conflicts like the one happening in Syria.

Again, you know, we have -- we have all interviewed militants who claim that they want to be Democrats for their people and then go back, you know, on their word, the Taliban and of course at the very beginning of the Islamic revolution in Iran.

You know, the West thought -- they believed Khomeini, who said he was going to be, you know, bring democracy, women's rights, human rights, et cetera.

What I want to ask you is this.

A lot of the leaders -- I was at the Doha forum where, you know, the Russians, the Iranians, the Turks, the -- you know, the Qataris, Saudis, everybody was there and they were all caught off guard.

But this is what the Qatari prime minister told me on stage.

Basically, they're all blaming Assad, right?

Everybody's throwing him and throwing him under the bus, saying that he was responsible for the fact that this offensive swept through like, you know, a hot knife through butter.

Here's what he told me.

While we had an opportunity in that time when the war over there has calmed down, yet Assad didn't seize this opportunity to start engaging and restoring his relationship with his people.

And we didn't see any serious movement, whether it's on the return of the refugees, or on reconciling with his own people.

Rami Jarrah, I wonder what you make of that.

Do you think there was ever a chance, even when the war, you know, got quiet for the last several years, that Assad could have rebuilt, knitted, responded to the legitimate demands of the Syrian people?

You know, I'm going to say something that might sound a bit strange, but I'm actually glad that he didn't strike a deal with Turkey at least, because Turkey is -- if we take a look at the sort of -- the conditions that are set on the table for negotiations between Turkey and Syria, Turkey essentially wanted to hand over the north back to Assad.

And I think Assad's refusal to do that or -- you know, there were disputes on some of the demands that Turkey was making, such as how deep the buffer zone that Turkey wanted into Syria.

Turkey wanted, I think, 30 kilometers, whereas Assad was demanding six and then went up to nine.

But I think Assad was actually trying to avoid this altogether, because he didn't have -- his state didn't have the capacity to actually govern Syria or take back all of these refugees, especially that the vast majority of them would be people that oppose his government.

So, I think Turkey was basically trying -- was on a path that was unrealistic.

It had nothing to do with the aspirations of the Syrian people.

And right now, it sounds strange to say, but I think that Jolani actually has -- HGF has the opportunity and these rebel groups seeming that they no longer depend solely on Turkey as being the border that they share with another state.

The fact that they have control over most of Syria right now is a sign that they can be independent and they don't have to depend on Turkey or give in to Turkey's conditions.

One point -- one really important thing to point out is the divisions between Arabs and Kurds in Syria and what countries actually play a major role in that.

Turkey is the main instigator of these disputes.

And this is a reason that, I mean, even now, OK, we've managed to some extent disconnect the influence of Russia and Iran over Syria, but we should have just as much an intention to do that with Turkey as well.

Turkey has its aspirations.

They have expansion.

They're very concerned sort of international interlocutors who believe that Turkey probably looks at this as a major victory for its influence in that region.

Can I end by asking you about the terrible human rights record?

I mean, it's really absolutely shocking and certainly people of Bashar Assad and his family and his henchmen, we've seen people rushing to the notorious prisons in Damascus.

Many years ago, we broke the story of Caesar and the pictures he, you know, bravely brought to the world.

It is quite extraordinary now to watch people rush to that prison to try to find news of their loved ones.

How do you feel when you're seeing these on social media and on video?

I haven't cried in years, literally years.

And these scenes have been the most emotional scenes for Syrians.

I think that the past five or six years, I speak for myself here, I think I represent quite a few people.

As Syria became a hopeless case for Syrians, especially those that left the country, like myself, there was always this sense of guilt towards, obviously, the people that have been killed, but a continuous guilt for those that remained in Assad's dungeons, watching prison after prison, entire prisons being freed.

It was exhilarating.

I think I haven't cried so much in so long, like a baby.

And it's just -- I don't -- I really don't have the words, Christiane.

The amount of pain the people have gone through.

I have friends who right now are frantic.

Some people, unfortunately, are still waiting to see.

There was an effort going on right now in Sednaya prison, where there were people trapped, basically, in -- they could see them on the CCTV, and they don't know where they are in the prisons, because the guards basically locked -- they disconnected the electrical system before they left, and they stopped the ventilation.

It's just even when they were leaving, it was criminal.

And the things that we're seeing in these prisons, there were children as babies in these prisons.

Thousands of women just left to rot in these prisons.

It's just unbelievable that what's happening right now is a vindication for the Syrian people, one that was desperately needed.

I think Syrians are traumatized.

We've become scapegoats on the international level, even in domestic affairs in Europe and the West.

We've become scapegoats for domestic problems.

And racism, I think this is a sort of vindication.

We've been given our country back.

And we have the opportunity now to build it and build a country that represents all of Syria, something that just under two weeks ago was literally impossible.

It is really remarkable.

And we thank you for your testimony and all that you did through the civil war to report what was going on there.

Rami Jarrah, thank you very much indeed.

Now, as we just were discussing, these most notorious prisons have been forced open.

Thousands of inmates suddenly find themselves free.

Thanks to the courage of one man, the actual horror chambers of Assad's prison system were revealed to the world a few years ago.

Between 2011 and 2013, a former military photographer known only as Caesar smuggled shocking evidence of war crimes out of Syria.

He had been ordered to photograph tortured, starved and burnt bodies inside regime jails.

But at great risk to himself, he made copies, 50,000 of them.

And back in 2014, we on this program, along with the Guardian newspaper, broke this news and broadcast the terrible evidence.

And three years later, I spoke to the still anonymous photographer in his first TV interview.

This clip contains some of Caesar's photos, and of course, they are graphic.

Caesar, can you tell me what your job was and why you decided to publicize, to smuggle out these pictures?

I used to work inside the military police with a group of other photographers that have different specialties.

Our job before the revolution, we took pictures of accidents.

If somebody was killed, if there was a suicide, if there was someone who drowned or if there was a fire.

Part of our work in the forensic evidence section is to go and to document these accidents and to work with the judges and the detectives from the military police.

But after the beginning of the revolution, after 2011, my work changed in a very full fundamental way.

We were no longer taking pictures of accidents or suicides or a drowning.

All of our work, for me and for my team, was to take pictures of martyrs, of prisoners that were detained in the Assad jails.

When did you realize that your job had changed?

And were there many, many more bodies that you were photographing on a regular basis than before the revolution?

There were small numbers at first, at the beginning of the revolution.

We would take in a day 10 to 20 people, sometimes 5 to 10 bodies that we would get daily.

But as the revolution went on, at the beginning of 2012, for example, the number started going up in a very marked way.

We started taking photos of 20, then 30, until it came to a point where we were taking like 50 or more bodies every day by 2013, for example.

Caesar, we are seeing really horrible pictures.

We have them projected on our wall here.

These are the pictures that you smuggled out.

What were the causes of death that you were recording?

Most of the bodies that we were taking photos of were of people that, by the way, were peaceful people.

These are some of the people that just took part of the protests in Damascus and in Daraa, calling for freedom.

There was signs of sometimes them being shot.

And you can see many wounds in their heads, in their bodies, in their arms.

We began to take photographs of bodies that had all these signs of all types of torture, of starvation for long periods of time.

And there would be a doctor, and there would be a photographer, and there would be people from the security forces with us to go body by body.

And we would number them based on the number that they were murdered in.

Caesar, did you ever dare ask your superiors what was going on?

Who doesn't live in Syria doesn't understand the situation of how much fear existed within us.

Even the pathologist had a high level, a high rank, but he was terrified of the intelligence.

The intelligence officers that were with us, it was terrifying.

It was not allowed for us to ask any question.

You were doing this for two years.

What impact did it have on you personally?

I was horrified.

I was terrified every day of the job that I was doing.

I would look at the different horrendous ways that these individuals were slaughtered and tortured to death.

The only crime they had was that they called for their own dignity and for their own freedom.

And then I would picture my own self on the faces of these bodies and worry about my family being in their place.

And many times I saw people that I knew personally, but because of the horrendous torture that happened to them, it was hard for me to recognize them.

The images of torture were the worst that I've ever seen.

Very bloodthirsty regime.

And Cesar had been, of course, testifying before Congress.

And anybody who wants to understand why there was this civil war, why there was a revolution that deposed Assad in the end, only has to listen to him and only has to look at those photos.

And for years the United Nations tried in vain to stop all the bloodshed of the civil war.

But now Assad is gone.

He's escaped the fate of Muammar Gaddafi.

He's gone to safety.

The next hours and days are critical.

The United Nations Special Envoy for Syria, Guy Pearson, says it is a watershed moment in Syria's history.

And he's joining me now from Geneva.

Guy Pearson, I know you were listening to that.

I just want to ask you to just to comment on is there any wonder there was a revolution?

Is there any wonder that people rose up against this kind of barbarism, really?

What's your feeling?

No, frankly speaking, we know this from, of course, 2011, 2012, 2013.

This is when it started when the Syrian people rose up and demanded justice, peace and democracy.

And, of course, what you have just shown and it just proves that the enormous suffering that people have been going through, you know, the more than 100000 people that are still missing, maybe no, hopefully many of them have not been able to come out of the prisons.

But I'm afraid that there are still people we don't know where are and that are still missing.

And, you know, it's it we all, I think, are filled with grief that this was actually possible to happen.

And of course, it's a it's a day of celebration and joy for those who have managed to get out.

And we mourn those who have lost their lives and suffered during all those years.

You've been looking at this file for a long, long time.

The Syria issue.

Just remind people these were kids who rose up in the little town of Daraa who just wanted, as you said, a bit of reform.

They were swept away by the Arab Spring and they never even at the beginning asked for the overthrow of of the dictator.

They just wanted reform.

And remind us how he responded, which led to these 13 years of such cruelty.

You're absolutely right.

It started as peaceful demonstrations and they were for a few months.

Hope that it could end peacefully.

Also, I've had a couple of addresses to the parliament during the spring of 2011 where people were hoping that he would address the real concerns that didn't happen.

And then it very quickly got violent.

And then we saw also then that the opposition got armed and it ended in a brutal civil war with most probably more than five hundred thousand people killed at the height of the fighting.

They were in Syria more than twelve hundred different armed groups.

And of course, we then saw during those years the rise of Al-Qaeda or ISIS.

And we know what that led to also was suffering for the for the for the Syrian people.

So it was such an enormous tragedy that at the time, I think in 2011, no one could predict would be happening.

And as we've said, ad infinitum, nobody predicted the speed with which this current, you know, rebel offensive against Assad took place.

So you were at the Doha Forum this weekend.

I was there as well.

You obviously met with high level foreign ministers from all the related countries.

What have you all decided?

And you called for a transitional government.

What are all the regional actors doing?

And by the way, who do you all think Al-Jolani is?

HTS is what they will actually do as governors.

Very, very good questions.

Remind me so I don't miss the second part of the question.

Let me start with the international community.

I think the you know, so as you rightly said, I discussed with the Iranian, the Russian, the Turkish foreign ministers, and also with the Egyptian, the Saudi, the Iraqi, the Jordanian and of course, the Qatari.

And I think all understood the seriousness of the situation.

And this is important.

The possibilities that this could be a new opening for the Syrian people, turning the page and the new opening to a new Syria that could be inclusive of all.

But for that to happen, you know that there needed to be immediate de-escalation, that we should not see a fight between the different armed groups that have now entered into Damascus.

And also taking into account that, of course, there are parts of the country that are not under the control of these armed groups.

We have the coast where we have mostly Alevites, but also others who are living with Russian bases.

And then, of course, we have the northeast with the Kurdish and the so-called SDF, the American protection.

So there are many, many issues that are not sorted out.

But to get and but to get this off to a good start, it's important that these groups know how to cooperate, but also that they send the message that they will establish a transitional body that is inclusive of all communities in Syria, that no one will be excluded.

And so far, we are luckily enough, we have been able to see that the messaging coming out by and large have been positive from from the armed groups.

But what is extremely important now is that we actually see that this is implemented on the ground.

And if that is happening, then I'm hopeful that this could really be a page that is turned and that we could see the emergence, hopefully soon, of a new and democratic Syria that really has been the aspirations for the Syrian people since 2011.

I mean, you know, the second question, that's it.

You covered it.

It was about Jolani.

And he's also said to our CNN's, you know, Jomana Karadsheh that he believes all, as he said, sects in Syria should be respected and and have their rights because there are so many.

But you know, the UN knows how Idlib was run under this these groups.

And you also know, as you said, that historically for the last 13 years anyway, there has been so much division between the various and and all sort of shades of who they are from the extremists to moderates.

What was it like in Idlib under HTS?

It was pretty hard line, I understand.

Yeah, it's you're absolutely right.

I mean, Idlib was run by an Islamist group, no doubt about it.

But my message is the following.

Syria cannot be run like Idlib.

And as you rightly pointed out, the messaging coming out from Jolani, among other places in the interview he gave to the CNN, should be reassuring.

But what is important now is that we see that this is implemented practically in the governance on a daily basis.

And so what what is the good news is that I hear this is not coming from Syrians across the border.

This is the message to the armed groups in Damascus.

Listen, let's not start fighting against each other again.

And it's also a message coming from a united international community.

So when I was in Doha, we had late Saturday night, we had a meeting between the Arab foreign ministers and the Iranian and the Turkish and the Russians.

And we all agreed on this message.

I think this this is a good beginning.

Of course, it's not a guarantee because in the end, it will be the Syrians themselves who decides this, hopefully with the support of the international community.

Geir Pedersen, UN envoy for Syria.

Thank you so much indeed, for joining us.

Really important information there.

Now, some of the war's worst fighting happened in Aleppo, which is Syria's second largest city.

But just five days ago, as we all now know, it became the first city to fall to the rebels.

Back in 2016, I spoke to Dr. Farida from the city when it was under siege.

She was one of the last OBGYNs working in there.

Worried for her own safety, she wore a surgical mask to conceal her identity when we spoke.

I see you have no light there.

What's the situation?

Because I don't have electricity, no water, nothing in Aleppo.

Today I came home and I found my home partially destroyed, but I can't clean because there is no water.

And now there is no electricity.

I just go to hospital and charge my phone and do some operations and some emergency.

And then I came home to find everything is destroyed.

And the government army is there is about two kilometers between them and between my house.

So you know, the last time we talked before this offensive had really made so much progress, you told me that it was like living in a horror movie.

What is changing?

How is it changing?

It's worse.

It's worse.

Now, when I have been in the hospital in the morning, I saw one little child about three years in the operating room.

I find his shoe in the ground.

I give it to him, told him, my little boy, take your shoe.

He told me, no, I don't need it anymore.

I lost my leg.

It's always, it's in Aleppo, you can see these children every day.

I see one girl in the age of my girl, about seven or eight years, she lost one hand.

And you can imagine a little baby in this age can't live their childhood.

They have broken legs.

They have cut off their legs or their hands.

They have a colostomy.

They had some injuries.

They have burns.

You can imagine a child is still alive in this, like a disabled.

That was eight years ago.

That suffering has been going on for so, so long.

Now a peaceful future beyond all of that is the hope for many right now, of course.

But it is uncertain as we've been discussing.

The U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin is warning that ISIS could attempt to take advantage of the situation.

And the United States has already bombarded their positions.

And up to now, the leader of HTS has had a $10 million U.S. bounty on his head.

Now, John Finer is the U.S. Deputy National Security Advisor, and he's joining us from the White House.

John Finer, welcome to the program.

So much suffering as we've been showing and so much hope that this will be ended now.

Just, you know, I know what the president has said, that it's an opportunity, but also potentially a challenge.

What are you all thinking in the White House?

Will you have any ability to steer the situation on the ground?

So, Christian, I think the president's words are quite important on this.

This is a momentous occasion, a moment that is full of significant opportunity for the Syrian people.

And that's a sentence you just could not say really at any point, certainly during the 13-year civil war and the generations of oppression and tyranny that preceded it.

But the dictator who perpetrated that conflict, Bashar al-Assad, is gone.

And so these people who have suffered so much now have an opportunity for a different form of governance and a different future.

That said, as the president said yesterday, and as I think your intro suggested, this is also a moment that is full of not insignificant risk.

Some of the groups that are involved in toppling Assad have their own quite checkered past.

ISIS, which the United States has dramatically diminished over the course of a decade of fighting that terrorist group, still exists in Syria.

And we will be vigilant to making sure that threat doesn't return.

And the United States has partners and allies along the border of Syria that are worried about the risk this could present to them.

So, first and foremost, as the president laid out, we're going to be standing with the Syrian people and trying to work towards the better future and shape this in the most constructive direction we can.

But it's not fundamentally about us.

It's really about them.

Yeah, and the United States has had a bit of a checkered history throughout this 13 years of civil war, not quite going all in, not pulling back, just under the famous red line that was crossed with impunity.

Your boss now, Jake Sullivan, the national security advisor, has said the following about working with the various groups on the ground.

Let me just play it.

We're going to work with all the groups in Syria.

And as President Biden said yesterday, the rebel groups, including the ones that have been designated as terrorist groups, have actually said all the right things.

Now the question is, what will they do to try to bring about a better Syria?

So I led into you, and I don't know whether it's still true.

You can tell me, you know, going on what Jake Sullivan just said, there has been a $10 million U.S. bounty on the head of al-Jolani, who's the head of HTS.

Is that still existing?

Are you going to remove it?

And are you in any way, shape, or form in touch or trying to send messages, trying to reach him for dialogue?

So, Christian, we have not yet in any way changed any formal policy with regard to the groups that toppled Assad, including with regard to the policies that you just described.

Those remain in place in large part because, as Jake Sullivan said and as the President said, we are not going to judge these groups based on what they have just done in terms of toppling Assad or in terms of some of the more constructive and positive things they've said, including on this very network, but on how they approach the greater responsibility that they are on the cusp of taking on.

In terms of whether we are able to convey direct messages to some of the groups involved, we have been able to convey those messages.

Beyond that, in terms of any sort of formal discussions, I don't have anything additional to describe at this point, but that's obviously something that is under consideration here.

John Finder, I'm sorry about the noise.

I know it must be distracting to you.

I don't know what's going on in the background, but in any event, you know, it seems to me, and correct me if I'm wrong, you're just saying we haven't been in touch with these people.

These are the people who are running things now in Syria.

It seems to me that the U.S. doesn't have a huge amount of leverage right now.

Clearly, Assad's backers were caught completely off guard, Russia and Iran, and they're busy withdrawing after 13 years of what apparently has been an incredibly bad investment.

You know, it's now the Kurds.

It's HTS.

It's, I mean, a whole number of alphabet soup groups there.

How do you really think this is going to play out?

And what, for instance, do you think Turkey has to gain?

It seems to be in the driving seat now.

So look, far be it for me to make predictions about how this is all going to play out, other than to reiterate that I think this is a tremendous moment of opportunity that has not been present for decades in Syria.

You rightly described there is a collection of groups, of ethnic groups, of sectarian groups, that are going to want and going to deserve a say in the future of how Syria is governed.

There's a Security Council resolution that's still on the books from 2015 that talks about inclusive governance for Syria, inclusive of all of the various communities that make up the Syrian state.

We think all of those communities should have a say in how the state is governed going forward.

We obviously have our close partners.

We're going to be watching out for their interest.

There are other outside countries, as you just described, that have played a role throughout this conflict.

But I do want to underscore one thing that you said just at the beginning of that question, which is the primary backers of Assad, the Russians and the Iranians, were completely caught off guard by this.

But that wasn't just a mistake and it wasn't just an accident with regard to Syria.

It was the result of policies that this administration and our partners pursued in other places, vis-a-vis the Russians in their war against Ukraine, where they have been badly weakened to the extent that they were unable to come to Assad's aid when he needed them in his time of peril.

And the Iranians, as a result of the strategic error they made post-October 7 to wage conflict throughout the Middle East and have been diminished, both they and their main proxy, Hezbollah, in the process.

That left them unable to come to Assad's aid.

So we want to make sure that that's not lost, the context in which this took place, even as it was these groups that ultimately overthrew Assad.

So let me quickly ask you about both of those, then.

Russia clearly has demonstrated that it can't fight two wars or a war in Ukraine and a rescue operation in Syria.

That's a big, serious statement about Russia's capabilities right now, isn't it?

Well, it's a good question for you to ask your next Russian interview subject when you have them on your show.

But from your perspective, because you're trying to prop up Russia's, you know, the people who Russia is backing.

Christian, we've been quite clear throughout the conflict in Ukraine that when it comes to partnering with Russia, when it comes to working with Russia, the conflict in Ukraine has shown what kind of a security partner Russia can be to other countries.

Its effectiveness on the battlefield was not what others expected it to be, including many people, we'll admit, inside our own government who expected Russia to run roughshod over the Ukrainians.

Because of their bravery and, frankly, because of many people overestimating the strength of the Russian army, Ukraine has performed far better than anybody had a right to expect.

And that influences Russia's other relationships, both in this region and around the world.

Now we have another data point.

A close Russian friend, one of its only real partners in the Middle East, has just been toppled without Russia so much as lifting a finger to provide help.

That is a signal that will be sent in this region and beyond.

Of course, they did extract Assad.

I'm not sure whether you have any opinions about that, but that's for another day.

But President-elect Trump has said in a statement that Syria is a mess, it's not our friend, the United States should have nothing to do with it, this is not our fight, let it play out, do not get involved.

I'm assuming you agree with that.

There's no U.S. plan to get involved on the ground in Syria, right?

I mean, you're there, you've got hundreds of troops there, will they stay?

That's what I was going to say.

So Christian, the United States is militarily on the ground in Syria for one purpose, and that is to fight ISIS, which posed a significant threat to the American people and to people around the world.

That mission continues, there continue to be U.S. forces very effectively suppressing the threat from ISIS, and we're going to continue to prioritize that.

Beyond that, you will not see U.S. forces get involved in the fighting in Syria.

I want to ask one question while I have you.

Obviously, the United States is trying to get a ceasefire, presumably, between Israel and Hamas to end the fighting in Gaza.

Does that seem more or less likely now?

And do you approve of Israel having gone in and basically taken over under the orders of Prime Minister Netanyahu, the military has taken the buffer zone between Syria and Israel?

Is that a long-term thing?

So on Gaza, President Biden and other U.S. officials have been quite clear that we believe that the ceasefire that we helped achieve in Lebanon between Israel and Hezbollah agreeing with us to conduct a ceasefire, that that should give momentum and that we are going to put more energy into trying to achieve a ceasefire in Gaza.

That process is still underway.

I'm not going to sit here and describe the intricacies of the negotiations in public, but we very much believe a ceasefire is possible, and it's a huge priority of this administration to try to achieve one, not least because it will get the hostages home who have been in this horrific condition for far too long.

In terms of what you described along Israel's border with Syria, it's been described by Israeli officials as a temporary measure, and I will leave it at that.

And one last question, because another big loser is Iran, right, with the fall of Assad.

So again, Americans believe that Assad had won this war, and you were trying, according to reports, to pull Assad away from Iran, to try to entice him away from Iran.

What do you think is going to be the fallout of the fact that he has fallen?

Does it mean that you or the next administration will try to go into a nuclear deal or what, or let them wither on the vine or let Israel attack their nuclear facilities?

What do you think is going to happen there?

So you're right that the Assad regime had effectively become a Russian-Iranian joint venture inside Syria, and both of those joint venture partners were no longer able to provide the support that the regime needed in order to survive, and that's a big part of why it's no longer in power.

But this is not the first loss that Iran has suffered over the course of the last year in the Middle East.

It's had two of its key proxies, Hamas and Hezbollah, badly diminished.

Its own attempts to strike Israel with ballistic missiles were defeated, in large part because of the support of the United States alongside the IDF in defending Israel from those threats.

So this is not a moment of strength for Iran, and what the implications are of that I'll let others speculate about, but that is, frankly, the result of work by the United States and our partners over the course of the last year that's brought us to that moment.

John Finer, deputy national security adviser, thank you so much for joining us from the White House on this day.

Now, for many Syrians, this, as we've said, is a time of hope, especially those whose loved ones were locked up by the regime.

Many now await news of their fate, and among them, an American family as well.

For 12 years, journalist Austin Tice has been missing in Syria, believed to have been arrested by the Assad regime.

His family believes he is alive.

And here's President Biden just after the rebels took Damascus.

We are mindful, we are mindful that there are Americans in Syria, including those who reside there, as well as Austin Tice, who was taken captive more than 12 years ago.

We remain committed to returning him to his family.

Now, as prisons across Syria empty, the Tice family are optimistic.

And I'm joined by Austin's sister, Abby, and his brother, Jacob.

Abby and Jacob, welcome to the family.

I see the T-shirts you are wearing.

And I want to know why your mother, for instance, has said that he is alive and he's being well treated.

What do you know?

Well, Christiane, thanks so much for having us.

We have heard from sources that have been vetted by the United States government that Austin is alive and that he has been well taken care of.

Those reports are recent, they are fresh, and we have every confidence that they are accurate.

Abby, how are you feeling?

You know, of course, we have lots of mixed emotions being here.

This is the first time our whole family has been together in Washington, D.C., and that it happens to be over this weekend where all of this is going on is just incredible and stressful and hopeful and just every emotion you can imagine.

How have you both been coping?

And your mother, I interviewed your mother and father, you know, several years ago.

And, you know, everybody, certainly the journalistic community, have been hoping and backing and, you know, activating and hopefully that he will be released.

How have you managed to cope?

I want both of you to tell me how, as a family, you have coped with this uncertainty.

I mean, you don't really have a choice.

You know, this is our brother.

We're never going to give up hope.

We're never going to stop fighting for him to come home.

It's been a long journey, and I will say my mom and my dad have really taken the lead, and they've protected us from a lot of what they've gone through in this last 12 years.

But, yeah, it's definitely been difficult to cope with what's been going on.

And Jacob, for you personally?

For me personally, I believe every day is a day that Austin should be released and a day that Austin could be released.

So I think thinking about it rather than in terms of years spent or months spent, that I have taken, you know, every day as its own day, a day that Austin could be released and a day that Austin should be released.

And that's the hope and optimism that I have lived in.

We believe that we are capable of bringing him home, that we, the United States, are capable of bringing Austin home.

And we have heard presidents, past, present, future presidents, talk about their commitment to bringing Austin home.

And those words are comforting.

And knowing that today and every day could be the day that he is released is a source of hope and optimism for me.

And Jacob, let me just ask you, because, you know, tell people who don't know Austin Tice.

I mean, he went to Syria to cover the war there.

And I think he was trying to drag you along with him.

How did it come to be that he went to Syria?

Austin has an adventurous spirit and a passion for shedding light in places that are, where light is difficult to reach.

And it was through those, under those principles that he went to Syria.

I think he reached out to me and asked me if I wanted to come to help, you know, join him in that adventure, to share that adventure with him.

I was in a different part of my life.

I have changed so much, you know, over the intervening 12 years.

And all I want now, all our family wants now is to be reunited with him, to bring him home, tell him about our family, introduce him to his nieces and nephews.

You know, this is what we want most of all.

You know, everything's changed since 2012, that's for sure.

And there are just so many tantalizing bits of information that the government seems to think that they have a, if not a lead, at least some way of knowing that he's alive.

I'm going to quote this from Jake Sullivan, the National Security Advisor, who said to Good Morning America today, this is a top priority for us to find Austin Tice, to locate the prison where he may be held, to get him out, get him home safely to his family.

And I believe that you were told in 2022 by President Biden that he knows with certainty that he, that Austin was being held by the Syrian government.

But the government, as you all know, have not publicly acknowledged that.

Abby, I wonder what you, whether you have any more detail on what the U.S. government knows, because the Syrian government hasn't publicly acknowledged it.

You know, we do know that the government knows that he is alive and he is in Syria.

And so we're hoping that since they're saying this is a top priority, that they truly make it one and that they use this opportunity to bring him home.

But yes, we do know that they know that he is alive and he is there.

And Jacob, you sort of alluded to various presidents because there have been three in office and maybe another one if he's not released before the next inauguration, it'll be four presidents, two of them the same one.

What sort of, how have you dealt with each administration or more to the point, how have they dealt with you?

Do you feel heard?

Do you feel, you know, that it is a priority?

We can, we as siblings have really let our mom, me in the driver's seat on those conversations.

Like Abby mentioned earlier, we have been somewhat insulated from those conversations.

I will say that we have heard repeatedly from all of those administrations how important Austin's case is to them, how they are making every effort, how their thoughts are always with him, how every conversation that they have about the region includes Austin Tyson.

We believe that now is the moment to act on those conversations, to take the appropriate actions to bring him home.

This is a singular moment in the region.

This is a unique and momentous time for Syria and it is a moment in which there are opportunities to bring Austin home.

And we implore both our government and anyone on the ground to help Austin get home, to find him, to secure him and to bring him home.

Abby, I don't know whether you have been also staying up to date with all the images of desperate Syrians going to the notorious prisons there, essentially the gulag system, to try to see if they could find loved ones and who they haven't heard from in decades.

Have you been keeping up to date with that?

Do you think Austin might be in one of those?

You know, we have been keeping up to date and the images are just absolutely incredibly sad, but also hopeful because these families are being reunited.

What I can speak to is that seeing these families reunited does give us hope that that can also be what happens for our family.

We know that he is there and so it is possible and we want that for our family as well.

And just talk a little bit more broadly, if you can, Jacob, about the work of journalists.

I mean, Austin went there to, I guess, try to make his name, telling the story about people who just wanted what everybody in the world wants, right?

Dignity, freedom, democracy, human rights, bread on the table, families to raise.

And this is what they got in return.

And journalists have been attacked throughout, you know, these last few years, terrible toll over the last year, particularly journalists in Gaza.

What do you think about the profession that he chose and the dangers?

I am so moved by the actions of his colleagues over the past 12 years.

We have seen an incredible fraternity of journalism, of journalists around the world who are passionate about Austin's case, who are passionate about helping our family, providing avenues of activism for us to take, for us to reach people with agency in these sorts of matters.

It has been so moving to have that instant understanding that what Austin was doing was important, that the work of journalists around the world is important, especially in places of conflict, in places where, you know, a beat journalist might not be able to go, where the news is hard to come by.

To have journalists in those places, sharing those stories, spreading that light is so critical.

And we have had nothing but sympathy and support and passion for Austin's cause from his profession.

And that is so moving to us and so important to us.

Well, honestly, we wish you all the best.

I spoke to your parents 12 years ago, just shortly after Austin went missing.

And I know how you've been keeping this in the public eye.

And clearly, at this time, we hope for you that you get your loved one back, just like we hope the same for all those Syrians who deserve a better future.

That's it for our program tonight.

If you want to know what's coming up every night, just go to our newsletter at pbs.org/amanpour.

Thanks for watching, and goodbye from London.

Support for PBS provided by: